Legacy Contaminants

Legacy Contaminants in and near the Mobile Tensaw Delta

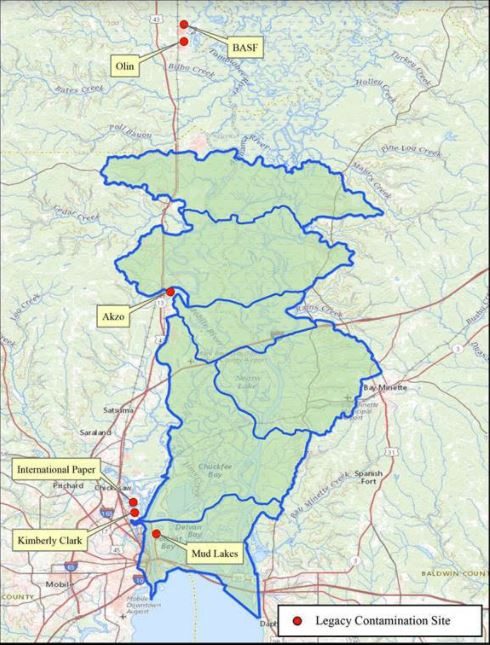

The Mobile-Tensaw-Apalachee (MTA) Watershed contains or is influenced by several sources of legacy contaminants, defined as originating from long-term industrial or commercial operations, and from which active release into the environment has ceased. Most of the chemical plants in and near the MTA Watershed were located there because of the presence of salt domes providing readily available chlorides needed for the mercuric-chloride reduction processes used to produce many chemical compounds. Sites originating legacy pollutants include the Stauffer Chemical Company (now Akzo-Nobel) chemical plant in Axis, the Alcoa Mud Lakes and International Paper Mill on the Mobile River and the Ciba-Geigy (now BASF) chemical plant in McIntosh.

Stauffer Chemical Company/Akzo-Nobel. A number of these facilities, especially Stauffer Chemical/Akzo-Nobel, released several different heavy metals into the Mobile River system or into forested wetlands and streams adjacent to the River. The primary contaminant of concern was mercury (Hg). Extremely high concentrations of Hg (up to 7,560 mg/kg) were found in Cold Creek Swamp (adjacent to the Stauffer Chemical plant), resulting in its designation as a Superfund site in 1984. The Hg concentrations observed in Cold Creek Swamp were deemed by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) to be too high to allow remediation through removal of the contaminated sediments. Instead, those sediments were sealed by an engineered cap and today remain in the floodplain. Mercury contamination in the Delta has led to fish consumption advisories since the early 1970s.

The Alcoa Mud Lakes were constructed on the east side of the Mobile River to receive waste sludge from the Alcoa plant that had been located on the west bank of the River. The EPA still requires monitoring, because these wastes contained a variety of heavy metals and caustic chemicals that continue to be released from the site as leachate from the leveed disposal area. While leachates are collected and treated to prevent releases into the River, some of these pollutants have accumulated in the sediments of Polecat Bay, on the east side of Blakeley Island, which receives most of the leachate.

Waste effluents from International Paper and Scott Paper (now Kimberly-Clark) contained a variety of chemicals, including dioxins. The two plants had a combined discharge of approximately 75 million gallons per day into Mobile River until operations at International Paper ended and operations at Kimberly-Clark were reduced (ca. 1999). Dioxin residues remain in the bottom sediments of the Mobile River and adjacent Mobile Bay. In areas where dioxin congeners exceed threshold levels set by the EPA, these residues can affect the ability of Mobile Harbor interests to perform dredging of new ship berths or maintenance dredging of existing navigation channels and pier areas, since the placement of dredged sediments is restricted to diked areas that have no return water. When the U.S. Coast Guard sought to restore a navigable channel at its Little Sand Island fire safety training facility in 2013, dioxin congener exceedances in sediments that had been deposited across the channel required creation of an upland diked area for placement of material excavated by clamshell dredge.

Arc Terminals. Proposed expansion of petroleum shipping operations at ARC Terminals in 2012 was limited to half the proposed amount of frontage improvement by dioxin congener exceedances in undisturbed Mobile River sediments, because no disposal site suitable for containing sediments contaminated by dioxin existed.

The Olin Chemical plant has produced organic compounds since 1956 and used the mercury cell process until 1981. The presence of elevated levels of mercury and other heavy metals in the soils and groundwater around the facility led to its designation in 1984 as a Superfund site. One of the key remediation measures implemented by Olin involves extraction and treatment of groundwater at numerous points around the property.

Ciba-Geigy (BASF) began producing DDT at its McIntosh facility in the mid-1950s. Some DDT wastes were discarded in the floodplain of the Tombigbee River, where they were susceptible to transport downstream during seasonal flooding. The facility was designated a Superfund site in 1984. Remedial measures at Ciba-Geigy included capping certain areas of high concentrations of DDT and derivatives in soils to prevent releases and bioaccumulation of these contaminants in fish and other biota in the floodplain.

Mobile Bay Causeway. The Alabama Department of Conservation and Natural Resources, State Lands Division funded a feasibility study of Mobile Causeway (Highway 90) restoration alternatives, which included a comprehensive analysis of sediment contaminant concentrations in areas just north and south of the Causeway (Weston, 2015). In Chocolatta Bay, 4,4’-DDT concentrations exceeded probable effects level (PEL) values at three stations: two located north of the Causeway and one located south of the Causeway. In Shellbank River, concentrations of arsenic, cadmium, copper, lead, mercury, nickel, and zinc were measured above TEL benchmarks. Metal exceedances occurred at four of six stations, whereas DDT compound concentrations were above ecotoxicological benchmarks at all Shellbank River sites (Weston, 2015).

Both DDT and its derivatives have been transported downstream into the Mobile-Tensaw Delta area, as reflected in sediment concentrations observed around the Mobile Causeway and in Mobile Harbor. The amount of this pollutant reaching the lower Delta should be decreasing as a result of the soil cap on top of the most-contaminated floodplain soils near the Ciba-Geigy chemical plant. Through monitoring of DDT and derivatives in fish populations that are restricted to the remediation site, evidence has shown that the soil cap has been very effective in reducing exposure of biota to the contaminants.

Alabama Power Barry Steam Plant Coal Ash Pond. In December 2008, a coal ash impoundment in Kingston, TN, experienced a catastrophic failure, spilling more than a billion gallons of coal ash slurry, contaminating more than 300 acres of land and both the Emory and Clinch rivers, and destroying local infrastructure. In response, the U. S. Environmental Protection Agency initiated the Coals Combustion Residuals (or CCR) Assessment Program in 2009, which assessed the structural integrity of over 500 coal ash impoundments nationwide. In 2015, the EPA Administrator signed the final Disposal of Coal Combustion Residuals (or CCR) Rule.

The CCR Rule regulated coal ash (deferring a determination of its status as “hazardous” or “nonhazardous,”) and required any existing CCR surface impoundment contaminating groundwater above a regulated standard to stop receiving CCR and to either retrofit or close. It also required the closure of any facility unable to meet the required location restrictions or structural integrity standards. Location restrictions on coal ash pons include those located:

- Within five feet of the uppermost aquifer,

- Within wetlands,

- Within 200 feet of active fault zones,

- In seismic impact zones, or

- In geologically unstable areas.

Since 1965, south Alabama’s James M. Barry Electric Generating Plant has disposed of 21,700,000 cubic yards of its coal ash waste (four times the volume of the Kingston spill) in a 597-acre settling pond located a bend in the Mobile River. Surrounded by a dike constructed to withstand a 1,000-year, 24-hour rainfall event within, this coal ash pond fails to meet several of the restrictions imposed by the Final Rule. This unlined impoundment sits within five feet of the uppermost aquifer within wetlands, and sampling reveals it is contaminating groundwater in excess of protection standards. Therefore, the Rule compelled Alabama Power to close the pond using one of two options: 1) The pond can be closed in place, drying the ash, and encapsulating it with a cover to keep water out, or 2) it can be closed by transporting the ash to a modern lined landfill. Any further coal ash disposals had to be moved to such a lined facility or recycled.

The Alabama Department of Environmental Management required Alabama Power to submit their closure plan for approval. They were fined for exceedances of the heavy metals arsenic and cobalt monitoring revealed in the ground water. They agreed to pay the fine and address groundwater contaminant concentrations by removing water from the ash, closing the pond, and providing regular monitoring reports for ADEM to track their progress in mitigating the contamination. Alabama Power developed a plan to close and cap the coal ash pond in place rather than transport the material to a lined landfill. The plan includes removing the water from the ash and treating it at an onsite wastewater treatment facility, excavating the coal ash and moving it back from the river and reducing its footprint by 45%, creating a redundant inner dike system surrounding the ash for containment and flood protection.

On June 23, 2020, the MBNEP publicly released a short film, The Unintended Consequences of Convenience - The Story of Coal Ash in Alabama. This animated feature is the culmination of a year of intensive research into the EPA’s Disposal of CCR Rule and Alabama Power’s Plan to close-in-place the Plant Barry coal ash pond. During the course of research and production of the film, MBNEP gathered extensive literature related to the CCR Rule and closure options and contracted two firms to conduct independent analyses of Alabama Power’s Closure Plan: Cook Hydrogeology, who assessed geologic and hydrologic factors underlying the Plan, and D’Apollonia Engineers, who reviewed factors related to structural integrity aspects of that Plan. MBNEP began development of this film after being approached by stakeholders and elected officials seeking information on Alabama Power’s plan to close-in-place the coal ash pond at Plant Barry.

View Full Press Release